The Washington Post

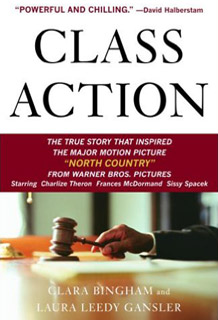

While Anita Hill was testifying against Clarence Thomas, another case of sexual harassment was making history. In 1991, Jenson v. Eveleth Mines wrested a landmark ruling from the courts that granted women employees the right to sue as a class. The details of the case, largely glossed over at the time, are the subject of Class Action by Clara Bingham and Laura Leedy Gansler. The book chronicles the decade-long struggle of Lois Jenson and her co-workers to get their employer, Eveleth Mines, to react to the treatment they were getting. As the authors make brilliantly, horrifyingly clear, the kind of behavior these women were subjected to isn’t teasing or pressuring or flirting that goes too far. This is brutality. This is terrorism.

Jenson started work in 1975 at the Eveleth iron mines in northern Minnesota. On her second day of work, a man walked by her, and “neither looking at her nor breaking his stride he said, ‘You [expletive] women don’t belong here. If you knew what was good for you, you’d go home where you belong.’ ” One man she had started dating taunted her in front of his friends and later, as she squatted to handle a heavy weight, grabbed her between her legs hard enough to knock her over, leaving a big handprint on her crotch.

The women were subjected daily to dirty jokes, dildoes, obscene graffiti. A man ejaculated on a woman’s sweater in her locker. Two women were driven by a co-worker to a remote location and were [probably] about to be assaulted when luck intervened. Another was stalked by a co-worker who left her explicit notes describing what he’d like to do to her. One man twisted a woman’s nose between his knuckles until blood streamed down her face. Another hit her in the arm and “called her names like bitch, [expletive] and whore.”

Unable to get help from the union or management, Jenson brought suit. She was vilified not just by the men but by the women, too, trying to protect their jobs. During 10 years of litigation, she and her co-plaintiffs endured opposing counsels’ psychological torture. And there was no Erin Brockovich ending. After the judge awarded skimpy damages, the case went to appeal, and in the end, the plaintiffs settled. But the confidentiality agreement meant the women were now scorned for their presumed wealth. “We never got a chance to set the record straight,” Jenson said.

Class Action has the formidable job of creating a story out of a case of relatively arcane significance, with a huge cast of characters, a lengthy and complicated time span, and a relentlessly demoralizing narrative. But Bingham and Gansler have come up with mesmerizing, complex portraits of the participants in a beautifully paced narrative. Their reporting is impeccable. The prose may at times be plain, but that’s the price of choosing verifiable facts over imagined drama. The story is dramatic enough.

The Los Angeles Times

Imagine working in an iron mine in northern Minnesota. You’re a single mother, 27 years old, on welfare. The only way you see to support yourself and your young son is by taking a mine job, which pays nearly three times what you might earn in any other employment available to women and offers health insurance. You are among the first four women hired to work in the mine–a result of affirmative action–and although the labor is backbreaking, you can do it. What you hadn’t counted on when you took the job in 1975 was the hostile work environment you’d be entering, where men resented women miners–women belonged at home, was the male rallying cry, not stealing men’s jobs. The men were ruthless in their angry, crude form of harassment: groping the female miners, threatening them, posting sexually explicit drawings in the workplace, yelling obscenities, stalking.

Class Action is the tightly written, extensively researched, and well-plotted account of the first sexual harassment class action suit, started by Lois Jenson, who walked naively into Eveleth Mines and one of the ugliest job environments imaginable, an environment the mining company refused to clean up until it was forced to take action nearly 25 years later. By then, Jenson had been joined by a handful of other female miners, making up the class that sued and eventually settled the case, and in the process, established crucial legal precedent. But the ordeal also cost her: Jenson’s physical and mental health deteriorated to an alarming degree.

Co-written by Clara Bingham, a journalist, and Laura Leedy Gansler, a lawyer versed in dispute resolution, Class Action combines potent narrative tension with copious research and legal information. Piecing together the ordeal with the pacing of a novel, they engage the reader from the outset; we are outraged by the behavior of particular men and incredulous that the mining company could consistently turn a blind eye, certain that a resolution must be on the horizon and then unbelieving that something so evident could take so long to rectify. Finally, reader and miners are beaten down by a legal system that allows victims to be re-victimized in court. The writing is never didactic. The human-interest element keeps readers fascinated and turning pages to see how, when–and sometimes if–the abuse would end.

Fascinating, as well, is the book’s exploration into the history of sexual harassment law and affirmative action. It was not until 1976 that the courts recognized sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which “prohibits employers from discriminating against workers on the basis of race, religion, color, national origin or sex.”

That bill, though, was originally aimed at fighting discrimination against African Americans and did not initially include gender as a category for potential discrimination. It was added only when Howard Smith, a congressional leader of the Southern conservatives who’d opposed the bill, “tacked on what he disparagingly called the ‘sex’ amendment, prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex.” The Virginia congressman “assumed that making employment discrimination against women a federal violation would be so unpopular that it would sink the bill.”

Clearly, he miscalculated, but the fact that gender discrimination wasn’t even part of the original antidiscrimination act is a telling detail. The authors’ use of this kind of eye-opening background places Jenson’s struggle in a historically accurate light and gives readers an understanding of the heroism behind the protection workers receive today.

Although the harassment the women faced in the workplace was clearly egregious, the most abusive situation presented in the book is that of our legal system and the damage it wreaked upon the plaintiffs’ personal lives as they fought for their rights. The judges of the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals, upon overturning an earlier ruling in the case, made this ironic statement on the miscarriage of justice: “If our goal is to persuade the American people to utilize our courts as little as possible, we have furthered that objective in this case.”

Eventually, a twisted sort of justice was carried out. On the verge of a jury trial, an out-of-court settlement was reached in December 1997 and the women were paid amounts averaging $233,000. By the time it was all over, the mining company and its insurers had spent more than $15 million in a losing effort to defend their right to maintain a hostile work environment. Still, it wasn’t really justice. “We never got a chance to set the record straight,” Jenson said afterward, a sentiment echoed by another plaintiff. “We just wanted to be believed.” This book, with its day-by-day recapitulation of what the women endured, is that opportunity.